The identity and rage of Hong Kong locals

”Are you press? What are these questions for? My English is more social, so you better speak to someone else.”

His English is impeccable, but I’m a foreigner and he doesn’t really understand what the Association of Foreign Affairs is. It’s election day in Hong Kong, and despite the streets being packed with activists calling out for action and handing out pamphlets, the rules are clear: no photos showing faces, no recorded interviews. They don’t know who I am, and I could be anyone.

So I decide to walk away from the red side and up to the blue; maybe my luck will change there. And it does – a young girl starts answering my questions. She tells me her candidate wants to separate Hong Kong from China. China is controlling their country, she says. I ask her if she believes her candidate, a young woman in a smart dress, can change it. She replies that Hong Kong is small, but her candidate will definitely bring some changes.

“We’ve had enough of China controlling us. We’re all students here, and we feel like a team. All of us, all Hong Kong students, want to bring forth a change. And together, we can do it.”

I took a cable car up to the giant Buddha close to the world’s smallest Disney Land the other day. Opposite the European group sat an elderly Cantonese couple. They immediately started talking politics to me. The woman, recently retired, asked if my friend and I could see the difference between Mainland Chinese and Hong Kong Chinese people.

“I am Chinese,” she told me. “But I don’t call myself Chinese. First and foremost, I am from Hong Kong. We don’t like them coming here. They immigrate, and they use our benefits. A real Hong Kong resident would never do that. We liked it much better when the British ruled.”

Her opinions reminded me of those I hear back home as well. It seems like no matter where you are in the world someone thinks immigration is a big problem.

Even though I spend most of my day at IKEA to find a new bedside lamp, I run into activist after activist on the streets and by the MTR entrances. This election is very important to the Hong Kong residents. My friends patiently wait as I find one more person who wants to answer my questions, or rather, take over the conversation.

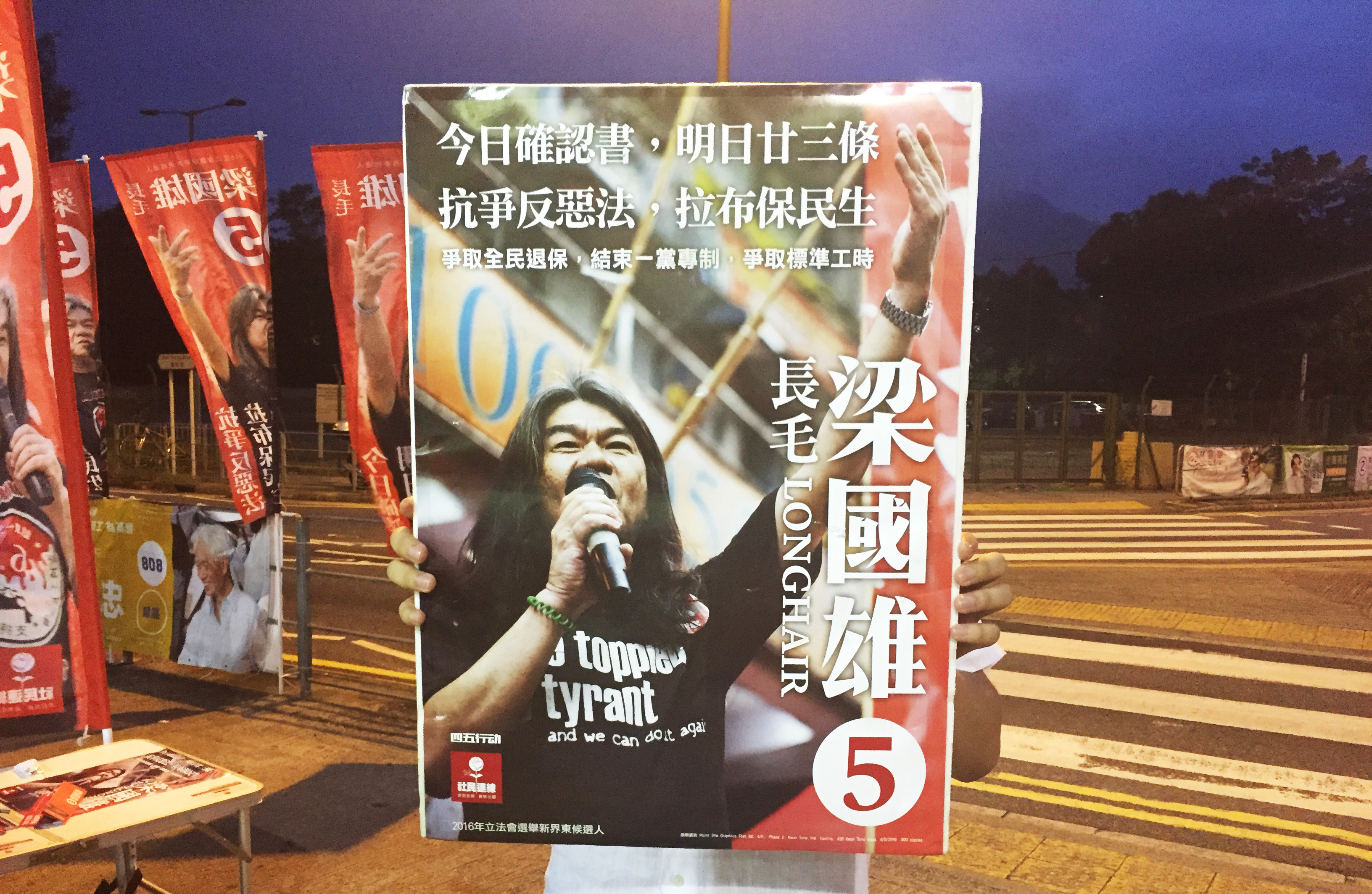

“How long are you in Hong Kong for?” he asks me. I tell him I’m here for four months. He tells me the timing of my stay is bad, because after the umbrella revolution the Chinese government have tried to control the independence movement. The candidate he promotes, he tells me, is leftist and has done much to help the poor. He also wants independence.

“We are moving towards a dictatorship in Hong Kong. This guy is anti-government. The current party has too many ties to the Chinese government and they need to step down.”

It’s Tuesday. We’ve gone to a local Cantonese place to eat oyster pancake and lemon chicken. I talk to my friend, who lives off campus in an apartment with his girlfriend and two local girls. He tells me the corruption in connection to this election is outraging his roommates. Voters get the wrong stamps on their ballets, making their votes invalid. The queues to the boots are made longer than needed, and independence voters receive the wrong papers. They’re outraged, and they’re sick of the situation. Every young person I talk to in Hong Kong seems to believe the same thing: change is necessary. The political system, the voting system and the establishment all need reforms.

So why don’t the pro independence movements have more power? My lecturer tries to explain the very complicated situation to me in broken English. According to Article 26 of the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, permanent residents of Hong Kong can vote in direct elections. In these elections, they can vote for the 35 seats representing geographical constituencies and 35 seats from a functional constituency. Some votes are worth 400 times other votes’ value. The franchise for the 30 seats left is limited to about 230,000 voters in the other functional constituencies. Depending on the business, some votes are worth a lot more than others. It’s a complicated system, and it works in favor of a lucky few.

Being where the action is is not common when you’re born in a small town in Sweden, and this is one of the few times when I am actually experiencing something. But it doesn’t feel the way I expected. My friend from home messaged me because he was worried, since he had heard that there were protests and unrest in Hong Kong. I tell him I’m fine. There is outrage, yes, but I seem to be standing in the eye of the storm, where you can’t hear a single breeze. Or perhaps, as a foreigner, just out of grasp of the action.

This blog post was written by Julia Bergström, Head of Career. She is currently doing her work in the UPF from Hong Kong. To find out more about the career committee, click here.